Describing Scenery, Clothing, And Other Details

how do I describe things in my stories? Like clothing, room, characters etc. it feels I put in too much detail. And is it also necessary to always describ new scenary? For example, when a character goes to their friends house the first time, is it necessary to describe the rooms they enter? Because I want my readers to be able to visualise properly but it feels as though I'm overflowing them with information sometimes

Describing Scenery, Clothing, and Other Details

The amount of description varies from one author to a next, and how much or little (or often) you describe things will be part of your unique writing style. However, you definitely don't want to overwhelm the reader with a bunch of unnecessary detail. So, really the key is to do two things: give the reader just enough detail that they can fill out the rest, give the reader details that are important.

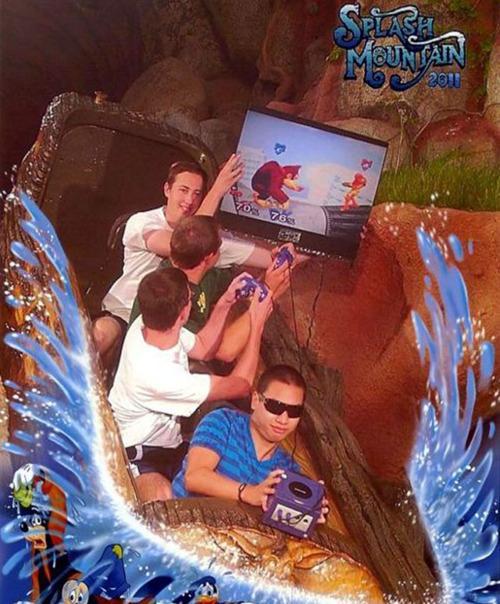

Give the Reader Just Enough Detail - Human brains are amazing. We're generally good at filling in missing details. If I show you the following image:

... your brain is perfectly capable of imagining the rest. You can imagine the mountain peaks and the rest of the lake. You don't need to see them to understand they're there and imagine what they look like.

That said, if I say, "Brenda appeared, wearing her signature torn jeans and favorite band t-shirt..." that's a pretty good image of what this person is wearing. The reader doesn't need to know what cut or color the t-shirt is, whether it's tucked in or loose, what band is depicted or what the specific design is, what color and cut the jeans are, where the holes are, what shoes they're wearing... none of that matters unless it does.

Give the Reader the Details That Are Important - If it's important that Brenda is wearing tennis shoes because later she'll be identified in a security video because of those shoes, then that then becomes an important detail you'd want to include in that description. Otherwise, don't bother. The reader doesn't need to know she's wearing white high-tops unless that's important for some reason.

So, when a character enters a new place or encounters a character for the first time (or encounters them in a new scene/situation), you want to give a little bit of detail to help the reader imagine what they should be seeing in their mind's eye. You also want to give them any details that are important for them to know later. You just don't want to overwhelm the reader with a bunch of unnecessary details.

Here are some other posts that will help:

Guide: Describing Character Appearance and Clothing The Right Amount of Description (5 Tips!) The 3 Fundamental Truths of Description Description: Style vs Excess/Deficiency Weaving Details into the Story How to Make Your Description More Vivid Adding Description to Your Writing

•••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••

I’ve been writing seriously for over 30 years and love to share what I’ve learned. Have a writing question? My inbox is always open!

LEARN MORE about WQA

SEE MY ask policies

VISIT MY Master List of Top Posts

COFFEE & FEEDBACK COMMISSIONS ko-fi.com/wqa

More Posts from Totallynotobsessedspades and Others

The Legendary Scarlett and Browne SPOILERS

Let's gooooo!!!!!!

Shhh.. They're communicating..

Tips for writing flawed but lovable characters.

Flawed characters are the ones we root for, cry over, and remember long after the story ends. But creating a character who’s both imperfect and likable can feel like a tightrope walk.

1. Flaws That Stem From Their Strengths

When a character’s greatest strength is also their Achilles' heel, it creates depth.

Strength: Fiercely loyal.

Flaw: Blind to betrayal or willing to go to dangerous extremes for loved ones.

“She’d burn the whole world down to save her sister—even if it killed her.”

2. Let Their Flaws Cause Problems

Flaws should have consequences—messy, believable ones.

Flaw: Impatience.

Result: They rush into action, ruining carefully laid plans.

“I thought I could handle it myself,” he muttered, staring at the smoking wreckage. “Guess not.”

3. Show Self-Awareness—or Lack Thereof

Characters who know they’re flawed (but struggle to change) are relatable. Characters who don’t realize their flaws can create dramatic tension.

A self-aware flaw: “I know I talk too much. It’s just… silence makes me feel like I’m disappearing.” A blind spot: “What do you mean I always have to be right? I’m just better at solving problems than most people!”

4. Give Them Redeeming Traits

A mix of good and bad keeps characters balanced.

Flaw: They’re manipulative.

Redeeming Trait: They use it to protect vulnerable people.

“Yes, I lied to get him to trust me. But he would’ve died otherwise.”

Readers are more forgiving of flaws when they see the bigger picture.

5. Let Them Grow—But Slowly

Instant redemption feels cheap. Characters should stumble, fail, and backslide before they change.

Early in the story: “I don’t need anyone. I’ve got this.”

Midpoint: “Okay, fine. Maybe I could use some help. But don’t get used to it.”

End: “Thank you. For everything.”

The gradual arc makes their growth feel earned.

6. Make Them Relatable, Not Perfect

Readers connect with characters who feel human—messy emotions, bad decisions, and all.

A bad decision: Skipping their best friend’s wedding because they’re jealous of their happiness.

A messy emotion: Feeling guilty afterward but doubling down to justify their actions.

A vulnerable moment: Finally apologizing, unsure if they’ll be forgiven.

7. Use Humor as a Balancing Act

Humor softens even the most prickly characters.

Flaw: Cynicism.

Humorous side: Making snarky, self-deprecating remarks that reveal their softer side.

“Love? No thanks. I’m allergic to heartbreak—and flowers.”

8. Avoid Overdoing the Flaws

Too many flaws can make a character feel unlikable or overburdened.

Instead of: A character who’s selfish, cruel, cowardly, and rude.

Try: A character who’s selfish but occasionally shows surprising generosity.

“Don’t tell anyone I helped you. I have a reputation to maintain.”

9. Let Them Be Vulnerable

Vulnerability adds layers and makes flaws understandable.

Flaw: They’re cold and distant.

Vulnerability: They’ve been hurt before and are terrified of getting close to anyone again.

“It’s easier this way. If I don’t care about you, then you can’t leave me.”

10. Make Their Flaws Integral to the Plot

When flaws directly impact the story, they feel purposeful rather than tacked on.

Flaw: Their arrogance alienates the people they need.

Plot Impact: When their plan fails, they’re left scrambling because no one will help them.

Flawed but lovable characters are the backbone of compelling stories. They remind us that imperfection is human—and that growth is possible.

TRC ANIMATIC :))

Idk what's happening my animatic keeps disappearing from tags, I'm trying to upload the yt version to see if it shows this time

If you come across this I hope you like it anyway :)

Guys!

I was so drowned with finals I slept less than 5 hours a night for two weeks,, but now I'm done. So I finished that animatic I started in December (what a bad idea to start this with that much work tbh), had so much fun doing it! All I could think of the last four weeks was this haha

I will finally add that the lyrics are very much linked to the scenes so make sure to listen to them

hi! I’m always looking for character design sheets/questionnaires to fill out for my characters, but I rarely find any I like. do you happen to have any suggestions?

Character Design Sheets/Questionnaires

(And My Alternative...)

While I think character design sheets/questionnaires can be fun to do, I also think they’re unnecessary and a bit of a time sink. After all, your character’s favorite kind of pizza won’t tell you much about who they are as a person, and probably doesn’t affect the plot at all.

In terms of fleshing out a character, I actually find it much more valuable to focus on the important things: Basic Biographical Details

Full Name: Nickname: Date of Birth: Gender: Description: Background Information Birthplace: Back Story: Current Residence: Occupation: Skills: Hobbies: Additional Details (If Applicable)

Aliases: Species: Powers: Crimes: Charges: Accomplices: Affiliation: Relationships

Parents: Siblings: Extended Family: Significant Other/s: Exes: Closest Friend: Friends: Coworkers: Classmates: Housemates: Neighbors: Impact Traits

Positive Traits: Negative Traits: Emotional Wound: Internal Conflict: Pre-Story Life Goals: Pre-Story Life Goals Motivation: Story Goal/s Story Goal/s Motivation: Stakes: Voice: Arc:

Fun Details

Quirks & Mannerisms: Hopes & Dreams: Likes & Dislikes: Clothing Style: Pet Peeves: Those are most of the big ones I worry about. Ultimately, if it doesn’t impact the story, character development, or truly help you understand who this character is, it’s not really important.

I hope that helps! <3

————————————————————————————————-

Have a question? My inbox is always open, but make sure to check my FAQ and post master lists first to see if I’ve already answered a similar question. :)

How to Improve Your Dialogue

As an editor, one of the biggest problems I see in beginning fiction writers’ dialogue is a lack of conflict.

(Come to think of it, one of the biggest problems I see in general is a lack of conflict, but that’s another post.)

Good dialogue, like a good story, should be rich with conflict. There are exceptions – most notably in a story’s ending or in brief, interspersed moments when you want to slow down the pace. But as a general guideline, dialogue without conflict gets boring very quickly. Here’s a classic example:

“Hi,” Lisa said. “Hey,” José said. “How are you?” “Fine. You?” “Doing all right.” Lisa handed José a turkey sandwich. “Would you like a sandwich? I made two.” “Sure, thanks.”

Okay, that’s enough. I won’t continue to torture you. Not only is there no conflict between the two characters who are speaking, but there’s no conflict anywhere to be seen.

The bad news is that if you write something like this you will bore your reader to tears.

The good news is that there are lots of ways to add conflict to dialogue. Once you know how to do it, you can make just about any scene pop with tension.

Of course, you don’t want to add conflict just for the sake of conflict. Whatever conflict you choose should be relevant to the story as a whole, to the scene, and to the characters.

Here’s my first tip: Have your characters say “No” to each other

One of the easiest ways to give conflict to a scene like this is to have your characters say No to each other, metaphorically speaking. In other words, to push back against the first character instead of just agreeing with them and refuse to have the conversation on the terms that the other character is proposing.

This is sometimes called giving characters different scripts.

Doing this creates an immediate power struggle that not only creates a more interesting story but can be really fun to play with. Here’s an example of how this idea could improve the scene between Lisa, Jose, and the sandwich:

“Hi,” Lisa said. “You forgot the mustard,” José said. Lisa thrust the turkey sandwich across the counter. “I’m fine, thanks. How are you?” “I don’t want it.” “I already made two. You should’ve said something earlier.”

Did you catch all the “No”s in that dialogue? Here it is again with my notes:

“Hi,” Lisa said. [Lisa is offering a friendly exchange.] “You forgot the mustard,” José said. [José refuses the offer and changes the subject.] Lisa thrust the turkey sandwich across the counter. “I’m fine, thanks. How are you?” [Lisa refuses to change the subject to the mustard, offers the sandwich as-is, and – bonus points – answers a question that hasn’t been asked.] “I don’t want it.” [José refuses to take the sandwich that’s been offered. Interestingly, though, he doesn’t try to take the power back in the situation by offering a new proposal, so he opens himself to a power grab from Lisa.] “I already made two. You should’ve said something earlier.” [Lisa acknowledges what José has said, but refuses to give into him by, for example, offering to make him another sandwich, add the mustard, etc.]

A big improvement, right? Dialogue like this makes us lean in and ask: What’s happening? Why are Lisa and José so testy with each other? What’s going to happen next? Will they make up? Will they come to blows?

If a scene like this comes midway through a story, we might already know that José is mad at Lisa because she didn’t come to the opening of his play last Saturday, and that Lisa, let’s say, has a bad temper and a history of throwing punches at José, in which case the dialogue becomes a great example of subtext.

Instead of having Lisa and José talk directly about the issue at hand (also called on-the-nose dialogue), we watch how the tension surfaces in their everyday interactions.

We get to become observers – flies on the wall – to their dramatic experience. In classic terminology, we are shown and not told the story.

Another thing to notice about this example is the use of gesture to enhance the dialogue’s conflict. Notice how when Lisa thrusts the turkey sandwich across the counter, it gives us information about her emotional state and implies a tone for the rest of her lines that we can hear without having to resort to clunky devices like “Lisa said sarcastically,” “Lisa said bitterly,” etc.

I have a few more tips about how to add conflict to your dialogue, but I will save it for another post. Hope this helps!

/ / / / / / /

@theliteraryarchitect is a writing advice blog run by me, Bucket Siler, a writer and developmental editor. For more writing help, download my Free Resource Library for Fiction Writers, join my email list, or check out my book The Complete Guide to Self-Editing for Fiction Writers.

ᴛɪᴘꜱ ꜰᴏʀ ᴡʀɪᴛᴇʀꜱ [ꜰʀᴏᴍ ᴀ ᴡʀɪᴛᴇʀ]

don't let your skill in writing deter you. publishers look for the storyline, not always excellent writing. many of the greatest books came from mediocre writers—and also excellent and terrible ones.

keep writing even when it sucks. you don't know how to write this battle scene yet? skip ahead. write [battle scene here] and continue. in the end, you'll still have a book—and you can fill in the blanks later.

find your motivation. whether it's constantly updating That One Friend or posting your progress, motivation is key.

write everything down. everything. you had the perfect plot appear to you in a dream? scribble down everything you can remember as so as you can. I like to keep cue cards on my nightstand just in case.

play with words. titles, sentences, whatever. a lot of it will probably change either way, so this is the perfect opportunity to try out a new turn of phrase—or move along on one you're not quite sure clicks yet.

explain why, don't tell me. if something is the most beautiful thing a character's ever laid eyes on, describe it—don't just say "it's beautiful".

ask for critique. you will always be partial to your writing. getting others to read it will almost always provide feedback to help you write even better.

stick to the book—until they snap. write a character who is disciplined, courteous, and kind. make every interaction to reinforce the reader's view as such. but when they're left alone, when their closest friend betrays them, when the world falls to their feet...make them finally break.

magic. has. limits. there is no "infinite well" for everyone to draw from, nor "infinite spells" that have been discovered. magic has a price. magic has a limit. it takes a toll on the user—otherwise why can't they simply snap their fingers and make everything go their way?

read, read, read. reading is the source of inspiration.

first drafts suck. and that's putting it gently. ignoring all the typos, unfinished sentences, and blatant breaking of each and every grammar rules, there's still a lot of terrible. the point of drafts is to progress and make it better: it's the sketch beneath an oil painting. it's okay to say it's not great—but that won't mean the ideas and inspiration are not there. first drafts suck, and that's how you get better.

write every day. get into the habit—one sentence more, or one hundred pages, both will train you to improve.

more is the key to improvement. more writing, more reading, more feedback, and you can only get better. writing is a skill, not a talent, and it's something that grows with you.

follow the rules but also scrap them completely. as barbossa wisely says in PotC, "the code is more what you'd call 'guidelines' than actual rules". none of this is by the book, as ironic as that may be.

write for yourself. I cannot stress this enough. if what you do is not something you enjoy, it will only get harder. push yourself, but know your limits. know when you need to take a break, and when you need to try again. write for yourself, and you will put out your best work.

Here’s Lapis! Technically it’s her in my glitch au but since we don’t have context yet I’ll just call her happy lapis :)

also should out to @albanenechi for their wonderful pose references!

-

theferalcollection reblogged this · 1 month ago

theferalcollection reblogged this · 1 month ago -

feralpaules liked this · 1 month ago

feralpaules liked this · 1 month ago -

cephalopadre liked this · 1 month ago

cephalopadre liked this · 1 month ago -

over-roaming-waves reblogged this · 1 month ago

over-roaming-waves reblogged this · 1 month ago -

texasdreamer01 reblogged this · 1 month ago

texasdreamer01 reblogged this · 1 month ago -

freyaishere-just liked this · 2 months ago

freyaishere-just liked this · 2 months ago -

morbidraven1321 reblogged this · 6 months ago

morbidraven1321 reblogged this · 6 months ago -

discoverywriter reblogged this · 6 months ago

discoverywriter reblogged this · 6 months ago -

discoverywriter liked this · 6 months ago

discoverywriter liked this · 6 months ago -

juuuuunaaaaaooooo reblogged this · 6 months ago

juuuuunaaaaaooooo reblogged this · 6 months ago -

skysides reblogged this · 9 months ago

skysides reblogged this · 9 months ago -

batri-jopa reblogged this · 11 months ago

batri-jopa reblogged this · 11 months ago -

jacqrosewrites liked this · 1 year ago

jacqrosewrites liked this · 1 year ago -

texasdreamer01 liked this · 1 year ago

texasdreamer01 liked this · 1 year ago -

fashiondemonnn liked this · 1 year ago

fashiondemonnn liked this · 1 year ago -

lizard-writes-things reblogged this · 1 year ago

lizard-writes-things reblogged this · 1 year ago -

inkdelicious liked this · 1 year ago

inkdelicious liked this · 1 year ago -

homicidal-idle reblogged this · 1 year ago

homicidal-idle reblogged this · 1 year ago -

farfromdaylight reblogged this · 1 year ago

farfromdaylight reblogged this · 1 year ago -

thunderboltfire liked this · 1 year ago

thunderboltfire liked this · 1 year ago -

kuru121 liked this · 1 year ago

kuru121 liked this · 1 year ago -

rayless-reblogs reblogged this · 1 year ago

rayless-reblogs reblogged this · 1 year ago -

daily-rayless liked this · 1 year ago

daily-rayless liked this · 1 year ago -

voidsumbrella liked this · 1 year ago

voidsumbrella liked this · 1 year ago -

runicmagitek reblogged this · 1 year ago

runicmagitek reblogged this · 1 year ago -

blue-logos reblogged this · 1 year ago

blue-logos reblogged this · 1 year ago -

baizzhu liked this · 1 year ago

baizzhu liked this · 1 year ago -

crymeariversworld liked this · 1 year ago

crymeariversworld liked this · 1 year ago -

lanasdiaryxo liked this · 1 year ago

lanasdiaryxo liked this · 1 year ago -

ladygreyish liked this · 1 year ago

ladygreyish liked this · 1 year ago -

rainbowconnex liked this · 1 year ago

rainbowconnex liked this · 1 year ago -

oasiswithmyg liked this · 1 year ago

oasiswithmyg liked this · 1 year ago -

haygirleyhay reblogged this · 1 year ago

haygirleyhay reblogged this · 1 year ago -

bouncehousedemons liked this · 1 year ago

bouncehousedemons liked this · 1 year ago -

november-moon-longing reblogged this · 1 year ago

november-moon-longing reblogged this · 1 year ago -

em-writes-stuff-sometimes reblogged this · 1 year ago

em-writes-stuff-sometimes reblogged this · 1 year ago -

pocketseizure liked this · 1 year ago

pocketseizure liked this · 1 year ago -

allthingssteddie liked this · 1 year ago

allthingssteddie liked this · 1 year ago -

somethingsomagicaboutwords liked this · 1 year ago

somethingsomagicaboutwords liked this · 1 year ago -

myulalie reblogged this · 1 year ago

myulalie reblogged this · 1 year ago -

paperbackribs reblogged this · 1 year ago

paperbackribs reblogged this · 1 year ago -

hiddenunderarock liked this · 1 year ago

hiddenunderarock liked this · 1 year ago -

sun-in-splendorhaditcoming liked this · 1 year ago

sun-in-splendorhaditcoming liked this · 1 year ago -

apartment8b liked this · 1 year ago

apartment8b liked this · 1 year ago -

runicmagitek liked this · 1 year ago

runicmagitek liked this · 1 year ago -

gywo reblogged this · 1 year ago

gywo reblogged this · 1 year ago -

space-boi-doesnt-write reblogged this · 1 year ago

space-boi-doesnt-write reblogged this · 1 year ago

90 posts