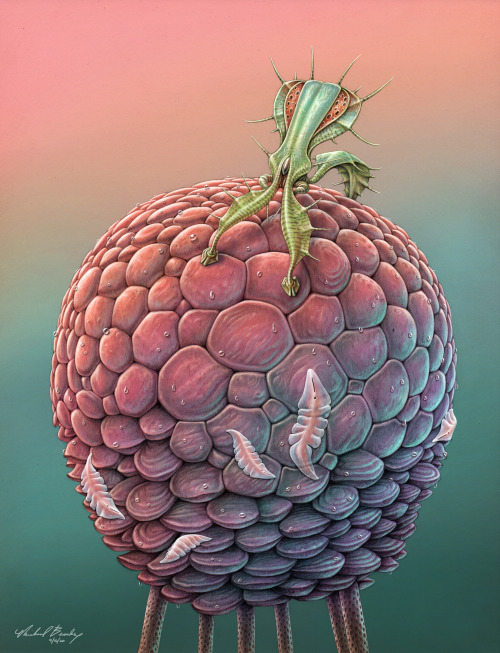

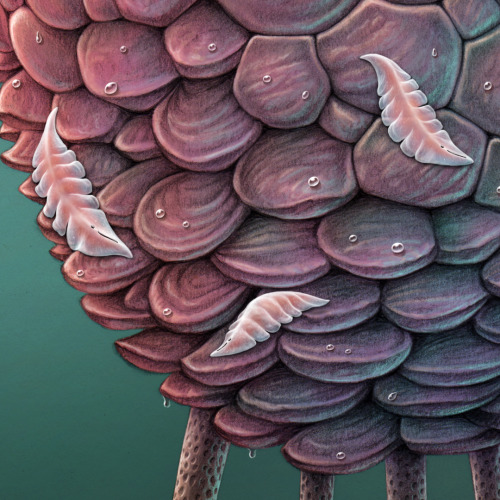

Guardian

Guardian

On Veteris, it is common for creatures to obtain energy from multiple sources. The large round, multifaceted autotroph angles its plates to face the light at any given time of day. It also feeds on decomposing organic matter it obtains by moving slowly on its long spindly legs. Conversely, the spiny guardian on top originally evolved to hunt the semi-transparent flat creatures that feed on the autotroph, but came to rely on them exclusively. Over many generations, individuals that allowed some prey items to live and reproduce eventually outlasted the more aggressive hunters, and now their style of subsistence is closer to farming. The guardians now protect the entire micro-system – each large round walker and its flock of parasites is topped by a spiny guardian who has the dual task of defending against predators as well as keeping the herd numbers in check. A round walker without a guardian slowly succumbs to parasite overpopulation. Occasionally huge numbers of walkers congregate in vast gently-swaying miniature forests, each crowned by a flamboyant spiny guardian defending its small world.

More Posts from Exobiotica and Others

Here is a nocturnal view of a habitat in which the inhabitants have evolved extreme forms of bioluminescence. The vertical glowing blobs are the reproductive bulb form of a species with a complex life cycle (to be elucidated in following artworks). The groove-backed, ravenous creatures at the bottom are of the same species as the glowing blobs, but at a different life stage. At center is a rather placid, slow-moving consumer of the bulbs- one who has incorporated its own form of bioluminescence into its respiratory apparatus as a means of camouflage. Names and descriptions will come as soon as possible.

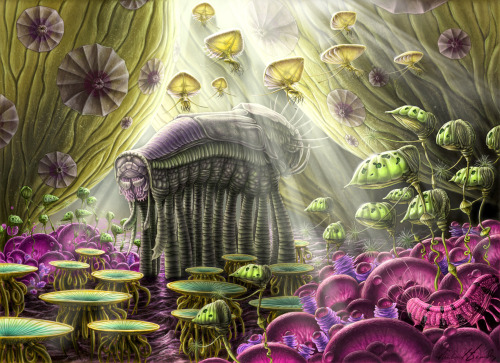

The Garden of Unearthly Delights

Biodiversity in Glow Forest Communities

Down on the floor of the Glow Forest, a startling array of lifeforms has evolved in the cool dark mist. The creatures that comprise the main structure of this biome are known as Vela, and they stretch skyward, consuming all the available sunlight and allowing none to escape below. This species won an evolutionary arms race long ago, and as a result its photosynthetic competitors were pushed to extinction. However being a successful monoculture has its disadvantages. Autotrophs form the base of the food chain in most environments, and now the Vela is the only one. This means it is now the main food source for many other species who would otherwise have more choices. Its main nemesis is the Stragulum. This amorphous creeping wrinkled blanket infects a new Vela pseudopod nearly as soon as it touches the ground. It rapidly takes hold and covers every inch of the surface, slowly digesting it. This in turn attracts a cadre of new organisms which consume the flesh of the Stragulum. Predators are then drawn to the area, and as the number of species grows, a self-perpetuating cycle of increasing biodiversity takes place. Eventually, the Stragulum becomes too much of a burden to the Vela and it severs its pseudopod in order to rapidly grow another nearby. But the biomass of the parasite still lingers for quite some time, feeding a plethora of bizarre and unique organisms scrambling for their share of the resources in this oasis of light amidst the darkness.

Interwoven

Like a giant pink warship, the Rosy Frigate punctuates the endless sea of tendrils. It hosts a crew of disk-shaped ravenous eating-machines called orbics. It is the orbics’ duty to keep the creeping tendrils from strangling and overtaking their home. Fading daylight signals their departure from the safe cluster beneath their giant companion to begin the night’s work of clearing new growth in the near vicinity. Each orbic can consume half its body weight in tube-carpet flesh every night, ensuring they will always have a place to return to at dawn. A Dwarf Blue Cortina observes the melee in confusion. Anything larger than an orbic will send it leaping away for cover, as its curiosity is matched only by its caution. The stoic quartet of Reponos standing solemnly in the background is incapable of seeing or hearing the events taking place nearby. Their role in this ecosystem turns out to be rather bizarre…

Cloud Grazers

Nubes comedenti

A family of Cloud Grazers seeks shelter from strong winds on the leeward side of a sheer rock face several hundred feet above the ground. Thanks to a lightweight body structure and internal hydrogen gas sacs, they are completely neutrally buoyant. Propelled by air jets on their sides, they are most at home at high altitude amongst the cliffs and mountain tops where they can hide from harsh weather and fierce predators. Most of their nutriment is obtained by way of their anterior filtration organs, which they extend while flying to sweep the sky of aerial biota - a sort of sky plankton.

Monolith

The seasonal rains have come to the high desert. Among the first to respond is the monolith. It sends out hose-like tendrils to siphon water and turns on its biolights to attract flying symbionts.

Grandulus

Trifasciatus grandulus

I should preface the description of this creature by giving a short statement about the natural history of its home planet. Early in its evolutionary history, life on this world did not split into such rigidly defined taxa as it did on Earth. For example, the majority of multicellular earth-life is divided into autotrophic creatures (plants) which are immobile, and the highly mobile heterotrophs (animals). On grandulus’s planet, the peculiar biochemistry allows for a much higher rate of horizontal gene transfer and endocytosis. This means that instead of a taxonomic “tree of life” like on Earth, their evolutionary history looks more like a web. In short, this allows for a wide array of photosynthetic, yet mobile creatures. The grandulus is one of these. It moves around slowly with its sticky appendages and positions itself in a spot with maximum sunlight to unfold its inflatable photosynthetic organ from its posterior shell. It also feeds on the internal fluids of metaflora, as well as decaying organic matter. Its many species range in size from that of a quarter to the size of a hippo.

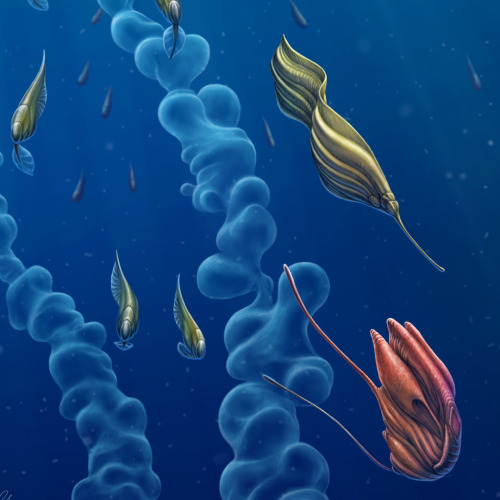

Back to the Depths

An entourage of opportunistic creatures accompanies the deep-sea behemoths during their brief ascent to the surface. Releasing their gelatinous strings of embryos here in the sunlight has a significant benefit - there's far more visibility. The swarm of followers are here in search of a quick meal in the form of the gelatin, which is full of valuable protiens and nutrients. After the feast however, the recipients of this apparent windfall become unwitting hosts for the behemoth's multitudinous offspring, which were embedded in the gel. Adapted to develop inside a wide variety of pelagic creatures, the young grow internally - and sometimes even on the surface of - their hosts until such time as they detach and sink back into the darkness. For most host species, this seems to be a mutually-beneficial symbiosis. At the beginning they receive a large and valuable meal, and usually incur very little detriment due to their temporary parasites. The young behemoths will hide in the dark depths for many years until attaining the size necessary to return to the light and repeat the ancient cycle again.

This is the native habitat of the megamyriapod (at center). This slow-moving, placid beast is about twenty feet tall and feeds primarily on the purple wave carpet organism that is spread across the floor of this scene- gathering it up with its anterior grasping appendages (at left). Other creatures lurk here, including the greenish motile floating feather duster gourds, the yellow/teal walking platter life-forms, and the purple pilantir balls. Growing around and above these smaller living things are the gargantuan lineated gold air-sponges - the megaflora that constitute the main physical features in this environment. All these creatures obtain energy from a combination of photosynthesis and physical consumption of soil nutrients or living tissue. Basically, the strict division of heterotroph/autotroph (plant/animal) that is exhibited by Earth-life simply does not apply here. Rather there is a gradient between those creatures who gain energy exclusively from light, and those who must consume others to survive. The majority of creatures here utilize both approaches.

Early India ink painting of an aquatic predator. (Un-named)

-

tundragravedigger reblogged this · 8 months ago

tundragravedigger reblogged this · 8 months ago -

tundragravedigger liked this · 8 months ago

tundragravedigger liked this · 8 months ago -

crimnsontroll liked this · 10 months ago

crimnsontroll liked this · 10 months ago -

ara6gir liked this · 10 months ago

ara6gir liked this · 10 months ago -

pixiesquid reblogged this · 10 months ago

pixiesquid reblogged this · 10 months ago -

lamehandle liked this · 10 months ago

lamehandle liked this · 10 months ago -

palewastelandking liked this · 11 months ago

palewastelandking liked this · 11 months ago -

jayjayzzzzzz liked this · 1 year ago

jayjayzzzzzz liked this · 1 year ago -

haru-dipthong liked this · 1 year ago

haru-dipthong liked this · 1 year ago -

erinmccomics liked this · 1 year ago

erinmccomics liked this · 1 year ago -

idontwannaliveinasociety liked this · 1 year ago

idontwannaliveinasociety liked this · 1 year ago -

shrillestceiling liked this · 1 year ago

shrillestceiling liked this · 1 year ago -

neddalian liked this · 1 year ago

neddalian liked this · 1 year ago -

crepuscular-girlthing reblogged this · 1 year ago

crepuscular-girlthing reblogged this · 1 year ago -

crepuscular-girlthing liked this · 1 year ago

crepuscular-girlthing liked this · 1 year ago -

johnofpannonia liked this · 1 year ago

johnofpannonia liked this · 1 year ago -

heywassap93 reblogged this · 1 year ago

heywassap93 reblogged this · 1 year ago -

magnificentsweetsdaze reblogged this · 1 year ago

magnificentsweetsdaze reblogged this · 1 year ago -

magnificentsweetsdaze liked this · 1 year ago

magnificentsweetsdaze liked this · 1 year ago -

jankiwen liked this · 1 year ago

jankiwen liked this · 1 year ago -

wtrotsky-blog liked this · 1 year ago

wtrotsky-blog liked this · 1 year ago -

astrobiology-and-astrophysics reblogged this · 2 years ago

astrobiology-and-astrophysics reblogged this · 2 years ago -

art-by-kvx liked this · 2 years ago

art-by-kvx liked this · 2 years ago -

plus-sizedscribe reblogged this · 2 years ago

plus-sizedscribe reblogged this · 2 years ago -

plus-sizedscribe liked this · 2 years ago

plus-sizedscribe liked this · 2 years ago -

blackstarbeneaththee reblogged this · 2 years ago

blackstarbeneaththee reblogged this · 2 years ago -

blackstarbeneaththee liked this · 2 years ago

blackstarbeneaththee liked this · 2 years ago -

spiffyspidr liked this · 2 years ago

spiffyspidr liked this · 2 years ago -

napalmtears liked this · 2 years ago

napalmtears liked this · 2 years ago -

andresfarias1 liked this · 2 years ago

andresfarias1 liked this · 2 years ago -

shinkei-shinto liked this · 2 years ago

shinkei-shinto liked this · 2 years ago -

throwaway-settings liked this · 2 years ago

throwaway-settings liked this · 2 years ago -

phol-kos reblogged this · 2 years ago

phol-kos reblogged this · 2 years ago -

narrole liked this · 2 years ago

narrole liked this · 2 years ago -

hibiscustoad liked this · 2 years ago

hibiscustoad liked this · 2 years ago -

itmewyrm liked this · 2 years ago

itmewyrm liked this · 2 years ago -

gray-science liked this · 2 years ago

gray-science liked this · 2 years ago -

fromthesuns liked this · 2 years ago

fromthesuns liked this · 2 years ago -

arachnid-archipelago liked this · 2 years ago

arachnid-archipelago liked this · 2 years ago -

marinara-biologist reblogged this · 2 years ago

marinara-biologist reblogged this · 2 years ago -

young-anxiety liked this · 2 years ago

young-anxiety liked this · 2 years ago -

yew--berries liked this · 2 years ago

yew--berries liked this · 2 years ago -

danacarajb liked this · 2 years ago

danacarajb liked this · 2 years ago -

metathinkingmachine liked this · 2 years ago

metathinkingmachine liked this · 2 years ago -

chaoskazz liked this · 2 years ago

chaoskazz liked this · 2 years ago -

catwolfsworld liked this · 2 years ago

catwolfsworld liked this · 2 years ago -

noodle-of-war liked this · 2 years ago

noodle-of-war liked this · 2 years ago -

samuelortezbignaturals liked this · 2 years ago

samuelortezbignaturals liked this · 2 years ago