Flawless. Gorgeous. Stellar.

Flawless. Gorgeous. Stellar.

You probably think this post is about you. Well, it could be.

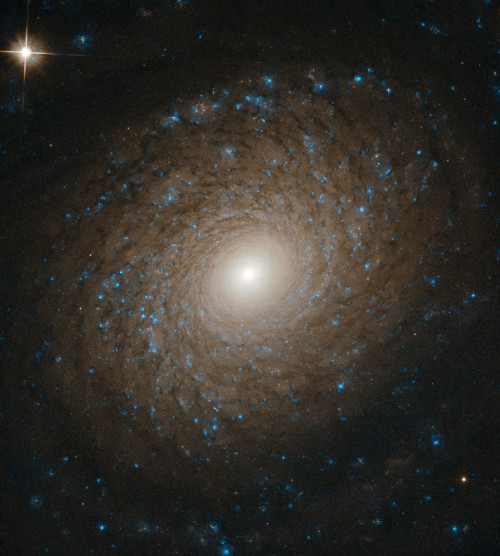

In this image taken by our Hubble Space Telescope, we see a spiral galaxy with arms that widen as they whirl outward from its bright core, slowly fading into the emptiness of space. Click here to learn more about this beautiful galaxy that resides 70 million light-years away.

Credit: ESA/Hubble & NASA, L. Ho Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com.

More Posts from Nasa and Others

Whats the best metaphor/ explanation of blackholes youve ever heard?

Houston, We Have a Launch!

Today, three new crew members will launch to the International Space Station. NASA astronaut Jeff Williams, along with Russian cosmonauts Alexey Ovchinin and Oleg Skripochka, are scheduled to launch from the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan at 5:26 p.m. EDT. The three Expedition 47 crew members will travel in a Soyuz spacecraft, rendezvousing with the space station six hours after launch.

Traveling to the International Space Station is an exciting moment for any astronaut. But what if you we’re launching to orbit AND knew that you were going to break some awesome records while you were up there? This is exactly what’s happening for astronaut Jeff Williams.

This is a significant mission for Williams, as he will become the new American record holder for cumulative days in space (with 534) during his six months on orbit. The current record holder is astronaut Scott Kelly, who just wrapped up his one-year mission on March 1.

On June 4, Williams will take command of the station for Expedition 48. This will mark his third space station expedition…which is yet another record!

Want to Watch the Launch?

You can! Live coverage will begin at 4:30 p.m. EDT on NASA Television, with launch at 5:26 p.m.

Tune in again at 10:30 p.m. to watch as the Soyuz spacecraft docks to the space station’s Poisk module at 11:12 p.m.

Hatch opening coverage will begin at 12:30 a.m., with the crew being greeted around 12:55 a.m.

NASA Television: https://www.nasa.gov/nasatv

Follow Williams on Social!

Astronaut Jeff Williams will be documenting his time on orbit, and you can follow along on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com

Whilst practicing solar distancing, Parker Solar Probe caught this rare glimpse of the twin tails on comet NEOWISE.☄

The twin tails are seen more clearly in this WISPR instrument processed image, which increased contrast and removed excess brightness from scattered sunlight, revealing more de-"tails". C/2020 F3 NEOWISE was discovered by our Near-Earth Object Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (NEOWISE), on March 27. Since it's discovery the comet has been spotted by several NASA spacecraft, including Parker Solar Probe, NASA’s Solar and Terrestrial Relations Observatory, the ESA/NASA Solar and Heliospheric Observatory, and astronauts aboard the International Space Station.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com

The Opportunity to Rove on Mars! 🔴

Today, we’re expressing gratitude for the opportunity to rove on Mars (#ThanksOppy) as we mark the completion of a successful mission that exceeded our expectations.

Our Opportunity Rover’s last communication with Earth was received on June 10, 2018, as a planet-wide dust storm blanketed the solar-powered rover's location on the western rim of Perseverance Valley, eventually blocking out so much sunlight that the rover could no longer charge its batteries. Although the skies over Perseverance cleared, the rover did not respond to a final communication attempt on Feb. 12, 2019.

As the rover’s mission comes to an end, here are a few things to know about its opportunity to explore the Red Planet.

90 days turned into 15 years!

Opportunity launched on July 7, 2003 and landed on Mars on Jan. 24, 2004 for a planned mission of 90 Martian days, which is equivalent to 92.4 Earth days. While we did not expect the golf-cart-sized rover to survive through a Martian winter, Opportunity defied all odds as a 90-day mission turned into 15 years!

The Opportunity caught its own silhouette in this late-afternoon image taken in March 2014 by the rover's rear hazard avoidance camera. This camera is mounted low on the rover and has a wide-angle lens.

Opportunity Set Out-Of-This-World Records

Opportunity's achievements, including confirmation water once flowed on Mars. Opportunity was, by far, the longest-lasting lander on Mars. Besides endurance, the six-wheeled rover set a roaming record of 28 miles.

This chart illustrates comparisons among the distances driven by various wheeled vehicles on the surface of Earth's moon and Mars. Opportunity holds the off-Earth roving distance record after accruing 28.06 miles (45.16 kilometers) of driving on Mars.

It’s Just Like Having a Geologist on Mars

Opportunity was created to be the mechanical equivalent of a geologist walking from place to place on the Red Planet. Its mast-mounted cameras are 5 feet high and provided 360-degree two-eyed, human-like views of the terrain. The robotic arm moved like a human arm with an elbow and wrist, and can place instruments directly up against rock and soil targets of interest. The mechanical "hand" of the arm holds a microscopic camera that served the same purpose as a geologist's handheld magnifying lens.

There’s Lots to See on Mars

After an airbag-protected landing craft settled onto the Red Planet’s surface and opened, Opportunity rolled out to take panoramic images. These images gave scientists the information they need to select promising geological targets that tell part of the story of water in Mars' past. Since landing in 2004, Opportunity has captured more than 200,000 images. Take a look in this photo gallery.

From its perch high on a ridge, the Opportunity rover recorded this image on March 31, 2016 of a Martian dust devil twisting through the valley below. The view looks back at the rover's tracks leading up the north-facing slope of "Knudsen Ridge," which forms part of the southern edge of "Marathon Valley

There Was Once Water on Mars?!

Among the mission's scientific goals was to search for and characterize a wide range of rocks and soils for clues to past water activity on Mars. In its time on the Red Planet, Opportunity discovered small spheres of the mineral hematite, which typically forms in water. In addition to these spheres that a scientist nicknamed “blueberries,” the rover also found signs of liquid water flowing across the surface in the past: brightly colored veins of the mineral gypsum in rocks, for instance, which indicated water flowing through underground fractures.

The small spheres on the Martian surface in this close-up image are near Fram Crater, visited by the Opportunity rover in April 2004.

For more about Opportunity's adventures and discoveries, see: https://go.nasa.gov/ThanksOppy.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com

Earth from Afar

“It suddenly struck me that that tiny pea, pretty and blue, was the Earth. I put up my thumb and shut one eye, and my thumb blotted out the planet Earth. I didn't feel like a giant. I felt very, very small.” - Neil Armstrong, Apollo 11

This week we're celebrating Earth Day 2018 with some of our favorite images of Earth from afar...

At 7.2 million Miles...and 4 Billion Miles

Voyager famously captured two unique views of our homeworld from afar. One image, taken in 1977 from a distance of 7.3 million miles (11.7 million kilometers) (above), showed the full Earth and full Moon in a single frame for the first time in history. The second (below), taken in 1990 as part of a “family portrait of our solar system from 4 billion miles (6.4 billion kilometers), shows Earth as a tiny blue speck in a ray of sunlight.” This is the famous “Pale Blue Dot” image immortalized by Carl Sagan.

“This was our willingness to see the Earth as a one-pixel object in a far greater cosmos,” Sagan’s widow, Ann Druyan said of the image. “It's that humility that science gives us. That weans us from our childhood need to be the center of things. And Voyager gave us that image of the Earth that is so heart tugging because you can't look at that image and not think of how fragile, how fragile our world is. How much we have in common with everyone with whom we share it; our relationship, our relatedness, to everyone on this tiny pixel."

A Bright Flashlight in a Dark Sea of Stars

Our Kepler mission captured Earth’s image as it slipped past at a distance of 94 million miles (151 million kilometers). The reflection was so extraordinarily bright that it created a saber-like saturation bleed across the instrument’s sensors, obscuring the neighboring Moon.

Hello and Goodbye

This beautiful shot of Earth as a dot beneath Saturn’s rings was taken in 2013 as thousands of humans on Earth waved at the exact moment the spacecraft pointed its cameras at our home world. Then, in 2017, Cassini caught this final view of Earth between Saturn’s rings as the spacecraft spiraled in for its Grand Finale at Saturn.

‘Simply Stunning’

"The image is simply stunning. The image of the Earth evokes the famous 'Blue Marble' image taken by astronaut Harrison Schmitt during Apollo 17...which also showed Africa prominently in the picture." -Noah Petro, Deputy Project Scientist for our Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter mission.

Goodbye—for now—at 19,000 mph

As part of an engineering test, our OSIRIS-REx spacecraft captured this image of Earth and the Moon in January 2018 from a distance of 39.5 million miles (63.6 million kilometers). When the camera acquired the image, the spacecraft was moving away from our home planet at a speed of 19,000 miles per hour (8.5 kilometers per second). Earth is the largest, brightest spot in the center of the image, with the smaller, dimmer Moon appearing to the right. Several constellations are also visible in the surrounding space.

The View from Mars

A human observer with normal vision, standing on Mars, could easily see Earth and the Moon as two distinct, bright "evening stars."

Moon Photobomb

"This image from the Deep Space Climate Observatory (DSCOVR) satellite captured a unique view of the Moon as it moved in front of the sunlit side of Earth in 2015. It provides a view of the far side of the Moon, which is never directly visible to us here on Earth. “I found this perspective profoundly moving and only through our satellite views could this have been shared.” - Michael Freilich, Director of our Earth Science Division.

Eight Days Out

Eight days after its final encounter with Earth—the second of two gravitational assists from Earth that helped boost the spacecraft to Jupiter—the Galileo spacecraft looked back and captured this remarkable view of our planet and its Moon. The image was taken from a distance of about 3.9 million miles (6.2 million kilometers).

A Slice of Life

Earth from about 393,000 miles (633,000 kilometers) away, as seen by the European Space Agency’s comet-bound Rosetta spacecraft during its third and final swingby of our home planet in 2009.

So Long Earth

The Mercury-bound MESSENGER spacecraft captured several stunning images of Earth during a gravity assist swingby of our home planet on Aug. 2, 2005.

Earth Science: Taking a Closer Look

Our home planet is a beautiful, dynamic place. Our view from Earth orbit sees a planet at change. Check out more images of our beautiful Earth here.

Join Our Earth Day Celebration!

We pioneer and supports an amazing range of advanced technologies and tools to help scientists and environmental specialists better understand and protect our home planet - from space lasers to virtual reality, small satellites and smartphone apps.

To celebrate Earth Day 2018, April 22, we are highlighting many of these innovative technologies and the amazing applications behind them.

Learn more about our Earth Day plans HERE.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com

Solar System: 10 Ways Interns Are Exploring Space With Us

Simulating alien worlds, designing spacecraft with origami and using tiny fossils to understand the lives of ancient organisms are all in a day’s work for interns at NASA.

Here’s how interns are taking our missions and science farther.

1. Connecting Satellites in Space

Becca Foust looks as if she’s literally in space – or, at least, on a sci-fi movie set. She’s surrounded by black, except for the brilliant white comet model suspended behind her. Beneath the socks she donned just for this purpose, the black floor reflects the scene like perfectly still water across a lake as she describes what happens here: “We have five spacecraft simulators that ‘fly’ in a specially designed flat-floor facility,” she says. “The spacecraft simulators use air bearings to lift the robots off the floor, kind of like a reverse air hockey table. The top part of the spacecraft simulators can move up and down and rotate all around in a similar way to real satellites.” It’s here, in this test bed on the Caltech campus, that Foust is testing an algorithm she’s developing to autonomously assemble and disassemble satellites in space. “I like to call it space K’nex, like the toys. We're using a bunch of component satellites and trying to figure out how to bring all of the pieces together and make them fit together in orbit,” she says. A NASA Space Technology Research Fellow, who splits her time between Caltech and NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), working with Soon-Jo Chung and Fred Hadaegh, respectively, Foust is currently earning her Ph.D. at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. She says of her fellowship, “I hope my research leads to smarter, more efficient satellite systems for in-space construction and assembly.”

2. Diving Deep on the Science of Alien Oceans

Three years ago, math and science were just subjects Kathy Vega taught her students as part of Teach for America. Vega, whose family emigrated from El Salvador, was the first in her family to go to college. She had always been interested in space and even dreamed about being an astronaut one day, but earned a degree in political science so she could get involved in issues affecting her community. But between teaching and encouraging her family to go into science, It was only a matter of time before she realized just how much she wanted to be in the STEM world herself. Now an intern at NASA JPL and in the middle of earning a second degree, this time in engineering physics, Vega is working on an experiment that will help scientists search for life beyond Earth.

“My project is setting up an experiment to simulate possible ocean compositions that would exist on other worlds,” says Vega. Jupiter’s moon Europa and Saturn’s moon Enceladus, for example, are key targets in the search for life beyond Earth because they show evidence of global oceans and geologic activity. Those factors could allow life to thrive. JPL is already building a spacecraft designed to orbit Europa and planning for another to land on the icy moon’s surface. “Eventually, [this experiment] will help us prepare for the development of landers to go to Europa, Enceladus and another one of Saturn’s moons, Titan, to collect seismic measurements that we can compare to our simulated ones,” says Vega. “I feel as though I'm laying the foundation for these missions.”

3. Unfolding Views on Planets Beyond Our Solar System

“Origami is going to space now? This is amazing!” Chris Esquer-Rosas had been folding – and unfolding – origami since the fourth grade, carefully measuring the intricate patterns and angles produced by the folds and then creating new forms from what he’d learned. “Origami involves a lot of math. A lot of people don't realize that. But what actually goes into it is lots of geometric shapes and angles that you have to account for,” says Esquer-Rosas. Until three years ago, the computer engineering student at San Bernardino College had no idea that his origami hobby would turn into an internship opportunity at NASA JPL. That is, until his long-time friend, fellow origami artist and JPL intern Robert Salazar connected him with the Starshade project. Starshade has been proposed as a way to suppress starlight that would otherwise drown out the light from planets outside our solar system so we can characterize them and even find out if they’re likely to support life. Making that happen requires some heavy origami – unfurling a precisely-designed, sunflower-shaped structure the size of a baseball diamond from a package about half the size of a pitcher’s mound. It’s Esquer-Rosas’ project this summer to make sure Starshade’s “petals” unfurl without a hitch. Says Esquer-Rosas, “[The interns] are on the front lines of testing out the hardware and making sure everything works. I feel as though we're contributing a lot to how this thing is eventually going to deploy in space.”

4. Making Leaps in Extreme Robotics

Wheeled rovers may be the norm on Mars, but Sawyer Elliott thinks a different kind of rolling robot could be the Red Planet explorer of the future. This is Elliott’s second year as a fellow at NASA JPL, researching the use of a cube-shaped robot for maneuvering around extreme environments, like rocky slopes on Mars or places with very little gravity, like asteroids. A graduate student in aerospace engineering at Cornell University, Elliott spent his last stint at JPL developing and testing the feasibility of such a rover. “I started off working solely on the rover and looking at can we make this work in a real-world environment with actual gravity,” says Elliott. “It turns out we could.” So this summer, he’s been improving the controls that get it rolling or even hopping on command. In the future, Elliott hopes to keep his research rolling along as a fellow at JPL or another NASA center. “I'm only getting more and more interested as I go, so I guess that's a good sign,” he says.

5. Starting from the Ground Up

Before the countdown to launch or the assembling of parts or the gathering of mission scientists and engineers, there are people like Joshua Gaston who are helping turn what’s little more than an idea into something more. As an intern with NASA JPL’s project formulation team, Gaston is helping pave the way for a mission concept that aims to send dozens of tiny satellites, called CubeSats, beyond Earth’s gravity to other bodies in the solar system. “This is sort of like step one,” says Gaston. “We have this idea and we need to figure out how to make it happen.” Gaston’s role is to analyze whether various CubeSat models can be outfitted with the needed science instruments and still make weight. Mass is an important consideration in mission planning because it affects everything from the cost to the launch vehicle to the ability to launch at all. Gaston, an aerospace engineering student at Tuskegee University, says of his project, “It seems like a small role, but at the same time, it's kind of big. If you don't know where things are going to go on your spacecraft or you don't know how the spacecraft is going to look, it's hard to even get the proposal selected.”

6. Finding Life on the Rocks

By putting tiny samples of fossils barely visible to the human eye through a chemical process, a team of NASA JPL scientists is revealing details about organisms that left their mark on Earth billions of years ago. Now, they have set their sights on studying the first samples returned from Mars in the future. But searching for signatures of life in such a rare and limited resource means the team will have to get the most science they can out of the smallest sample possible. That’s where Amanda Allen, an intern working with the team in JPL’s Astrobiogeochemistry, or abcLab, comes in. “Using the current, state-of-the-art method, you need a sample that’s 10 times larger than we’re aiming for,” says Allen, an Earth science undergraduate at the University of California, San Diego, who is doing her fifth internship at JPL. “I’m trying to get a different method to work.” Allen, who was involved in theater and costume design before deciding to pursue Earth science, says her “superpower” has always been her ability to find things. “If there’s something cool to find on Mars related to astrobiology, I think I can help with that,” she says.

7. Taking Space Flight Farther

If everything goes as planned and a thruster like the one Camille V. Yoke is working on eventually helps send astronauts to Mars, she’ll probably be first in line to play the Mark Watney role. “I'm a fan of the Mark Watney style of life [in “The Martian”], where you're stranded on a planet somewhere and the only thing between you and death is your own ability to work through problems and engineer things on a shoestring,” says Yoke. A physics major at the University of South Carolina, Yoke is interning with a team that’s developing a next-generation electric thruster designed to accelerate spacecraft more efficiently through the solar system. “Today there was a brief period in which I knew something that nobody else on the planet knew – for 20 minutes before I went and told my boss,” says Yoke. “You feel like you're contributing when you know that you have discovered something new.”

8. Searching for Life Beyond Our Solar System

Without the option to travel thousands or even tens of light-years from Earth in a single lifetime, scientists hoping to discover signs of life on planets outside our solar system, called exoplanets, are instead creating their own right here on Earth. This is Tre’Shunda James’ second summer simulating alien worlds as an intern at NASA JPL. Using an algorithm developed by her mentor, Renyu Hu, James makes small changes to the atmospheric makeup of theoretical worlds and analyzes whether the combination creates a habitable environment. “This model is a theoretical basis that we can apply to many exoplanets that are discovered,” says James, a chemistry and physics major at Occidental College in Los Angeles. “In that way, it's really pushing the field forward in terms of finding out if life could exist on these planets.” James, who recently became a first-time co-author on a scientific paper about the team’s findings, says she feels as though she’s contributing to furthering the search for life beyond Earth while also bringing diversity to her field. “I feel like just being here, exploring this field, is pushing the boundaries, and I'm excited about that.”

9. Spinning Up a Mars Helicopter

Chloeleen Mena’s role on the Mars Helicopter project may be small, but so is the helicopter designed to make the first flight on the Red Planet. Mena, an electrical engineering student at Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University, started her NASA JPL internship just days after NASA announced that the helicopter, which had been in development at JPL for nearly five years, would be going to the Red Planet aboard the Mars 2020 rover. This summer, Mena is helping test a part needed to deploy the helicopter from the rover once it lands on Mars, as well as writing procedures for future tests. “Even though my tasks are relatively small, it's part of a bigger whole,” she says.

10. Preparing to See the Unseen on Jupiter's Moon Europa

In the 2020s, we’re planning to send a spacecraft to the next frontier in the search for life beyond Earth: Jupiter’s moon Europa. Swathed in ice that’s intersected by deep reddish gashes, Europa has unveiled intriguing clues about what might lie beneath its surface – including a global ocean that could be hospitable to life. Knowing for sure hinges on a radar instrument that will fly aboard the Europa Clipper orbiter to peer below the ice with a sort of X-ray vision and scout locations to set down a potential future lander. To make sure everything works as planned, NASA JPL intern Zachary Luppen is creating software to test key components of the radar instrument. “Whatever we need to do to make sure it operates perfectly during the mission,” says Luppen. In addition to helping things run smoothly, the astronomy and physics major says he hopes to play a role in answering one of humanity’s biggest questions. “Contributing to the mission is great in itself,” says Luppen. “But also just trying to make as many people aware as possible that this science is going on, that it's worth doing and worth finding out, especially if we were to eventually find life on Europa. That changes humanity forever!”

Read the full web version of this week’s ‘Solar System: 10 Things to Know” article HERE.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com.

Hey! I was wondering how everyone on the ISS adjusts to each other’s culture and language. It seems like it might be hard with language barriers and other factors, to live in a confined space with people from another country. Do others try to teach you their language? Does everyone mostly speak English, or do some people speak Russian?

10 Things: Mars Helicopter

When our next Mars rover lands on the Red Planet in 2021, it will deliver a groundbreaking technology demonstration: the first helicopter to ever fly on a planetary body other than Earth. This Mars Helicopter will demonstrate the first controlled, powered, sustained flight on another world. It could also pave the way for future missions that guide rovers and gather science data and images at locations previously inaccessible on Mars. This exciting new technology could change the way we explore Mars.

1. Its body is small, but its blades are mighty.

One of the biggest engineering challenges is getting the Mars Helicopter’s blades just right. They need to push enough air downward to receive an upward force that allows for thrust and controlled flight — a big concern on a planet where the atmosphere is only one percent as dense as Earth’s. “No helicopter has flown in those flight conditions – equivalent to 100,000 feet (30,000 meters) on Earth,” said Bob Balaram, chief engineer for the project at our Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

2. It has to fly in really thin Martian air.

To compensate for Mars’ thin atmosphere, the blades must spin much faster than on an Earth helicopter, and the blade size relative to the weight of the helicopter has to be larger too. The Mars Helicopter’s rotors measure 4 feet wide (about 1.2 meters) long, tip to tip. At 2,800 rotations per minute, it will spin about 10 times faster than an Earth helicopter. At the same time, the blades shouldn’t flap around too much, as the helicopter’s design team discovered during testing. Their solution: make the blades more rigid. “Our blades are much stiffer than any terrestrial helicopter’s would need to be,” Balaram said. The body, meanwhile, is tiny — about the size of a softball. In total, the helicopter will weigh just under 4 pounds (1.8 kilograms).

3. It will make up to five flights on Mars.

Over a 30-day period on Mars, the helicopter will attempt up to five flights, each time going farther than the last. The helicopter will fly up to 90 seconds at a time, at heights of up to 10 to 15 feet (3 to 5 meters). Engineers will learn a lot about flying a helicopter on Mars with each flight, since it’s never been done before!

4. The Mars Helicopter team has already completed groundbreaking tests.

Because a helicopter has never visited Mars before, the Mars Helicopter team has worked hard to figure out how to predict the helicopter’s performance on the Red Planet. “We had to invent how to do planetary helicopter testing on Earth,” said Joe Melko, deputy chief engineer of Mars Helicopter, based at JPL.

The team, led by JPL and including members from JPL, AeroVironment Inc., Ames Research Center, and Langley Research Center, has designed, built and tested a series of test vehicles.

In 2016, the team flew a full-scale prototype test model of the helicopter in the 25-foot (7.6-meter) space simulator at JPL. The chamber simulated the low pressure of the Martian atmosphere. More recently, in 2018, the team built a fully autonomous helicopter designed to operate on Mars, and successfully flew it in the 25-foot chamber in Mars-like atmospheric density.

Engineers have also exercised the rotors of a test helicopter in a cold chamber to simulate the low temperatures of Mars at night. In addition, they have taken design steps to deal with Mars-like radiation conditions. They have also tested the helicopter’s landing gear on Mars-like terrain. More tests are coming to see how it performs with Mars-like winds and other conditions.

5. The camera is as good as your cell phone camera.

The helicopter’s first priority is successfully flying on Mars, so engineering information takes priority. An added bonus is its camera. The Mars Helicopter has the ability to take color photos with a 13-megapixel camera — the same type commonly found in smart phones today. Engineers will attempt to take plenty of good pictures.

6. It’s battery-powered, but the battery is rechargeable.

The helicopter requires 360 watts of power for each second it hovers in the Martian atmosphere – equivalent to the power required by six regular lightbulbs. But it isn’t out of luck when its lithium-ion batteries run dry. A solar array on the helicopter will recharge the batteries, making it a self-sufficient system as long as there is adequate sunlight. Most of the energy will be used to keep the helicopter warm, since nighttime temperatures on Mars plummet to around minus 130 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 90 Celsius). During daytime flights, temperatures may rise to a much warmer minus 13 to minus 58 degrees Fahrenheit to (minus 25 to minus 50 degrees Celsius) — still chilly by Earth standards. The solar panel makes an average of 3 watts of power continuously during a 12-hour Martian day.

7. The helicopter will be carried to Mars under the belly of the rover.

Somewhere between 60 to 90 Martian days (or sols) after the Mars 2020 rover lands, the helicopter will be deployed from the underside of the rover. Mars Helicopter Delivery System on the rover will rotate the helicopter down from the rover and release it onto the ground. The rover will then drive away to a safe distance.

8. The helicopter will talk to the rover.

The Mars 2020 rover will act as a telecommunication relay, receiving commands from engineers back on Earth and relaying them to the helicopter. The helicopter will then send images and information about its own performance to the rover, which will send them back to Earth. The rover will also take measurements of wind and atmospheric data to help flight controllers on Earth.

9. It has to fly by itself, with some help.

Radio signals take time to travel to Mars — between four and 21 minutes, depending on where Earth and Mars are in their orbits — so instantaneous communication with the helicopter will be impossible. That means flight controllers can’t use a joystick to fly it in real time, like a video game. Instead, they need to send commands to the helicopter in advance, and the little flying robot will follow through. Autonomous systems will allow the helicopter to look at the ground, analyze the terrain to look how fast it’s moving, and land on its own.

10. It could pave the way for future missions.

A future Mars helicopter could scout points of interest, help scientists and engineers select new locations and plan driving routes for a rover. Larger standalone helicopters could carry science payloads to investigate multiple sites at Mars. Future helicopters could also be used to fly to places on Mars that rovers cannot reach, such as cliffs or walls of craters. They could even assist with human exploration one day. Says Balaram: "Someday, if we send astronauts, these could be the eyes of the astronauts across Mars.”

Read the full version of this week’s ‘10 Things to Know’ article on the web HERE.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com.

Optical Communications: Explore Lasers in Space

When we return to the Moon, much will seem unchanged since humans first arrived in 1969. The flags placed by Apollo astronauts will be untouched by any breeze. The footprints left by man’s “small step” on its surface will still be visible across the Moon’s dusty landscape.

Our next generation of lunar explorers will require pioneering innovation alongside proven communications technologies. We’re developing groundbreaking technologies to help these astronauts fulfill their missions.

In space communications networks, lasers will supplement traditional radio communications, providing an advancement these explorers require. The technology, called optical communications, has been in development by our engineers over decades.

Optical communications, in infrared, has a higher frequency than radio, allowing more data to be encoded into each transmission. Optical communications systems also have reduced size, weight and power requirements. A smaller system leaves more room for science instruments; a weight reduction can mean a less expensive launch, and reduced power allows batteries to last longer.

On the path through this “Decade of Light,” where laser joins radio to enable mission success, we must test and demonstrate a number of optical communications innovations.

The Laser Communications Relay Demonstration (LCRD) mission will send data between ground stations in Hawaii and California through a spacecraft in an orbit stationary relative to Earth’s rotation. The demo will be an important first step in developing next-generation Earth-relay satellites that can support instruments generating too much data for today’s networks to handle.

The Integrated LCRD Low-Earth Orbit User Modem and Amplifier-Terminal will provide the International Space Station with a fully operational optical communications system. It will communicate data from the space station to the ground through LCRD. The mission applies technologies from previous optical communications missions for practical use in human spaceflight.

In deep space, we’re working to prove laser technologies with our Deep Space Optical Communications mission. A laser’s wavelength is smaller than radio, leaving less margin for error in pointing back at Earth from very, very far away. Additionally, as the time it takes for data to reach Earth increases, satellites need to point ahead to make sure the beam reaches the right spot at the right time. The Deep Space Optical Communications mission will ensure that our communications engineers can meet those challenges head-on.

An integral part of our journey back to the Moon will be our Orion spacecraft. It looks remarkably similar to the Apollo capsule, yet it hosts cutting-edge technologies. NASA’s Laser Enhanced Mission Communications Navigation and Operational Services (LEMNOS) will provide Orion with data rates as much as 100 times higher than current systems.

LEMNOS’s optical terminal, the Orion EM-2 Optical Communications System, will enable live, 4K ultra-high-definition video from the Moon. By comparison, early Apollo cameras filmed only 10 frames per second in grainy black-and-white. Optical communications will provide a “giant leap” in communications technology, joining radio for NASA’s return to the Moon and the journey beyond.

NASA’s Space Communications and Navigation program office provides strategic oversight to optical communications research. At NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, the Exploration and Space Communications projects division is guiding a number of optical communications technologies from infancy to fruition. If you’re ever near Goddard, stop by our visitor center to check out our new optical communications exhibit. For more information, visit nasa.gov/SCaN and esc.gsfc.nasa.gov.

Sending Science to Space (and back) 🔬🚀

This season on our NASA Explorers video series, we’ve been following Elaine Horn-Ranney Ph.D and Parastoo Khoshaklagh Ph.D. as they send their research to the space station.

From preparing the experiment in the lab….

To training the astronauts to perform the science…

To watching it launch to space…

To conducting the science aboard the space station, we’ve been there every step of the way.

Now you can follow along with the whole journey!

Binge watch all of NASA Explorers season 4: Microgravity HERE

Want to keep up with space station research? Follow ISS Research on Twitter.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com

-

samyroya liked this · 1 year ago

samyroya liked this · 1 year ago -

ereconda liked this · 2 years ago

ereconda liked this · 2 years ago -

ado0odi reblogged this · 2 years ago

ado0odi reblogged this · 2 years ago -

ado0odi liked this · 2 years ago

ado0odi liked this · 2 years ago -

infinoya liked this · 2 years ago

infinoya liked this · 2 years ago -

andromedaisfree reblogged this · 2 years ago

andromedaisfree reblogged this · 2 years ago -

andromedaisfree liked this · 2 years ago

andromedaisfree liked this · 2 years ago -

nlockett liked this · 3 years ago

nlockett liked this · 3 years ago -

nlockett reblogged this · 3 years ago

nlockett reblogged this · 3 years ago -

superlucyjin reblogged this · 3 years ago

superlucyjin reblogged this · 3 years ago -

canigohomenow02 liked this · 4 years ago

canigohomenow02 liked this · 4 years ago -

mileyflzliam reblogged this · 4 years ago

mileyflzliam reblogged this · 4 years ago -

live2succeed liked this · 4 years ago

live2succeed liked this · 4 years ago -

physicla liked this · 4 years ago

physicla liked this · 4 years ago -

lushdesirelines reblogged this · 4 years ago

lushdesirelines reblogged this · 4 years ago -

lushdesirelines liked this · 4 years ago

lushdesirelines liked this · 4 years ago -

miniaturedonutcashkid liked this · 4 years ago

miniaturedonutcashkid liked this · 4 years ago -

alexiiiis reblogged this · 4 years ago

alexiiiis reblogged this · 4 years ago -

elainenasa liked this · 4 years ago

elainenasa liked this · 4 years ago -

onechildishnerd liked this · 5 years ago

onechildishnerd liked this · 5 years ago -

webadventures15 liked this · 5 years ago

webadventures15 liked this · 5 years ago -

lilfungii reblogged this · 5 years ago

lilfungii reblogged this · 5 years ago -

lilfungii liked this · 5 years ago

lilfungii liked this · 5 years ago -

hironojp liked this · 5 years ago

hironojp liked this · 5 years ago -

k-llewellin-novelist reblogged this · 5 years ago

k-llewellin-novelist reblogged this · 5 years ago -

elysiabot reblogged this · 5 years ago

elysiabot reblogged this · 5 years ago -

kernsing reblogged this · 5 years ago

kernsing reblogged this · 5 years ago -

2020tybo liked this · 5 years ago

2020tybo liked this · 5 years ago -

pinkiepieaddict reblogged this · 5 years ago

pinkiepieaddict reblogged this · 5 years ago -

sablenight112 liked this · 5 years ago

sablenight112 liked this · 5 years ago

Explore the universe and discover our home planet with the official NASA Tumblr account

1K posts